22nd Chief, 6th Baronet of Morvern, 18th Laird of Duart, 2nd Lord Maclean*

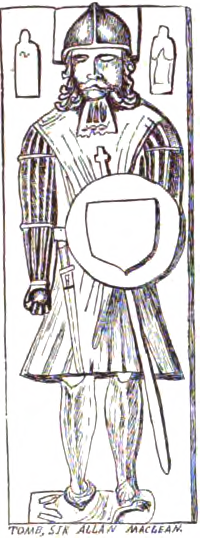

Brigadier-General Sir Allan Maclean, 6th Baronet of Morvern,1 18th Laird of Duart, 4th Laird of Brolas, 2nd Lord Maclean2 succeeded his cousin, Major Sir Hector Maclean, as the 22nd Chief of the Clan Maclean in 1750.3

Sir Allan’s chiefship is the first break in the direct line of succession.4 Both third cousin of his predicessor5 and great-grandson of the 15th Chief,1 Sir Allan was the rightful heir and scion of the Duart line.5 With Sir Allan’s succession, the Chieftainship of Brolas forever merged into the chiefly line of Duart.6

In 1749 Sir Allan succeeded his grandfather as 4th Laird of Brolas.7 Despite inheriting the Baronetcy of Morvern Sir Allan never petitioned the Lyon Court for matriculation of the Duart Arms, as would have been customary; but rather retained the Brolas Arms throughout his lifetime.7

After completing his education at the University of Glasgow,8 Sir Allan sought out a military career,4 and served with considerable distinction both in Europe and North America.1 Sir Allan is often confused with General Allan Maclean of Torloisk with whom he served in both Holland and the Americas.9 Sir Allan retired at the rank of Colonel1 after the Seven Years’ War. Throughout his life, Sir Allan is often referred to as “the Knight,”8 a nickname he seems to have picked up after his father’s passing.

Sir Allan was the last Maclean Chief to live in the Highlands for nearly two centuries, and was the was the last Maclean chief who could natively address his clan in their ancient Gaelic language. He is the subject of several Gaelic songs.7 Sir Allan was a, “good-looking man, of a frank disposition and polished manners; and, like Highland chiefs in general, liberal and hospitable.”7 Sir Allan was beloved by his clan and spoken of with great affection during his life and for many years thereafter.1

Service

1747c Captain, Scots Brigade, Drumlanrig’s Regmt.10

1756 Lieutenant, British Army, 77th Regiment of Foot11

1757 Captain, British Army, 77th Regiment of Foot12

1762 Major, British Army, 119th Regiment of Foot13

1763 Retired from active service in the British Army1

1772 Lieutenant-Colonel, British Army, Unattached14

1774c Colonel, British Army, Unattached4

Brigadier-General, British Army, Unattached15

Family

Sir Allan was born about 17107 to Donald Maclean of Brolas and Isabella Maclean,3 daughter of Allan MacLean, 10th Laird of Ardgour. Donald and Isabella were married shortly after the turn of the 18th18 century. Sir Allan’s father, who was a Lieutenant during the reign of Queen Anne, was severely wounded in the head by a trooper’s saber at the Battle of Sheriffmuir; having attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, he died in April of 1725 while Sir Allan was still a young man. Sir Allan had five siblings, Ann, Catherine, Gillean, Isabel, and James.3

In 1737, Sir Allan matriculated at the University of Glasgow as “Allanus McLean a Broloss in Insula de Mull.”8 In the 18th century, the typical age of students entering universities was 17,8 thus Sir Allan either began his education late, or was born later than it has been thought. Though he would always return home, this was the first of Sir Allan’s many extended absences from his homeland.

After returning from military service in Holland, Sir Allan married Una Maclean in 1750.8 Una was the fourth daughter of Hector, 11th Maclean of Coll;5 they had one son, Lachlan, who died in infancy19 and three daughters,4 Maria, Anna, and Sibbella.9 Maria married Charles Maclean of Kinlochaline. Sibella married John Maclean of Inverscadell and became a lady of high accomplishments; they resided near Cheltenham.5 Ann died unmarried.

Una died from a nervous fever on the 30th of May in 1760.7 Sir Allan was in North America with the 77th Foot Regiment of the British Army when learned of his wife’s death.1 Sir Allan took a leave of absence and returned to Great Britain to make arrangements for his children before returning to military service. Observing Una’s death in his diary, Alexander Maclean of Pennycross wrote, “That is the end of that family.”19

Military Service

Though born to a Maclean Chieftain, the Macleans had been dispossessed of their lands by Campbells more than a generation earlier; thus Sir Allan’s early life was one of limited means and with few prospects in the homeland of his ancestors.18 As did many of the highlanders after the ‘15 Jacobite Rising, Sir Allan saw that his opportunity for advancement lay in a military career.4 King George II was eager to enlist his rebellious subjects for military service abroad. Most of what is known about Sir Allan’s military service is from examining regimental records. Sir Allan’s military service took him to the mainland of Europe and to North America where he participated in various campaigns that won Canada for the British Empire.19

Jacobite Uprising of 1745

Melville Henry Massue records in his comprehensive work, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, that Sir Allan joined the Argyleshire Militia in 1745 to fight against Prince Charles’s attempt to restore the Stuarts to the throne.2 However there is no other record of Sir Allan participating on either side of the ‘45 Jacobite Rebellion.

“Tho’ the Knight has failings, want of friendship is none of his faults.”

– Gen. Allan Maclean of Torloisk,27 1764 –

Three facts call this record into question. First, by 1750, Sir Allan had attained the rank of Captain10 in the Scots Brigade while in the service of the Dutch. The rank of Captain, as a company-grade rank, implies having risen through the subaltern-grade ranks either by purchase or appointment. Since Sir Allan had not the means to purchase a company-grade commission, he would have earned his rank over time. Second, The Macleans were openly supporters of the Jacobites. Third, when Sir Allan sued the Duke of Argyll for the return of the lands of Brolas, Allan Maclean of Drimnin was the primary claimant because he had not participated in the ‘45 Rebellion and therefore was not prosecuted.19 Had Sir Allan fought for the Crown in the ‘45 Rebellion, there would have been no need for Allan Maclean of Drimnin to stand as claimant in the lawsuit. In all likelihood, Sir Allan was already in Holland when the ‘45 Rebellion broke out in Britain.

Scots Brigade in the Netherlands

The first reference to Sir Allan’s military career appears in July of 1747.20 Allan Maclean, Brolas, a Capt. of the independent companies

is the fifth senior captain listed on the roll of The Officers of Drumlanrig’s Regiment &c.9 Henry Douglas, Earl of Drumlanrig, raised a regiment of 2 battalions which he commanded from 1747-1751.1 Drumlanrig’s regiment augmented the 3 old regiments of the Scots Brigade4 which numbered 6,000 men strong in 1747.21 Loaned to the Dutch Republic by Britain, the Scots Brigade operated as a separate organization within the Dutch army.10

(War of Austrian Succession)

Sir Allan served in the 2nd Battalion of Drumlanrig’s regiment7 during the War of Austrian Succession.10 The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle ended hostilities of the War of Austrian Succession. The additional troops of Drumlanrig’s regiment were no longer needed, and thus the regiment was reduced to a single battalion. Sir Allan appears in the Dutch army list of 1750 after the reduction.10 Sometime after 1750, Sir Allan took leave of the Scots Brigade and returned home to the Island of Mull7 on half-pay.3

Seven Years War

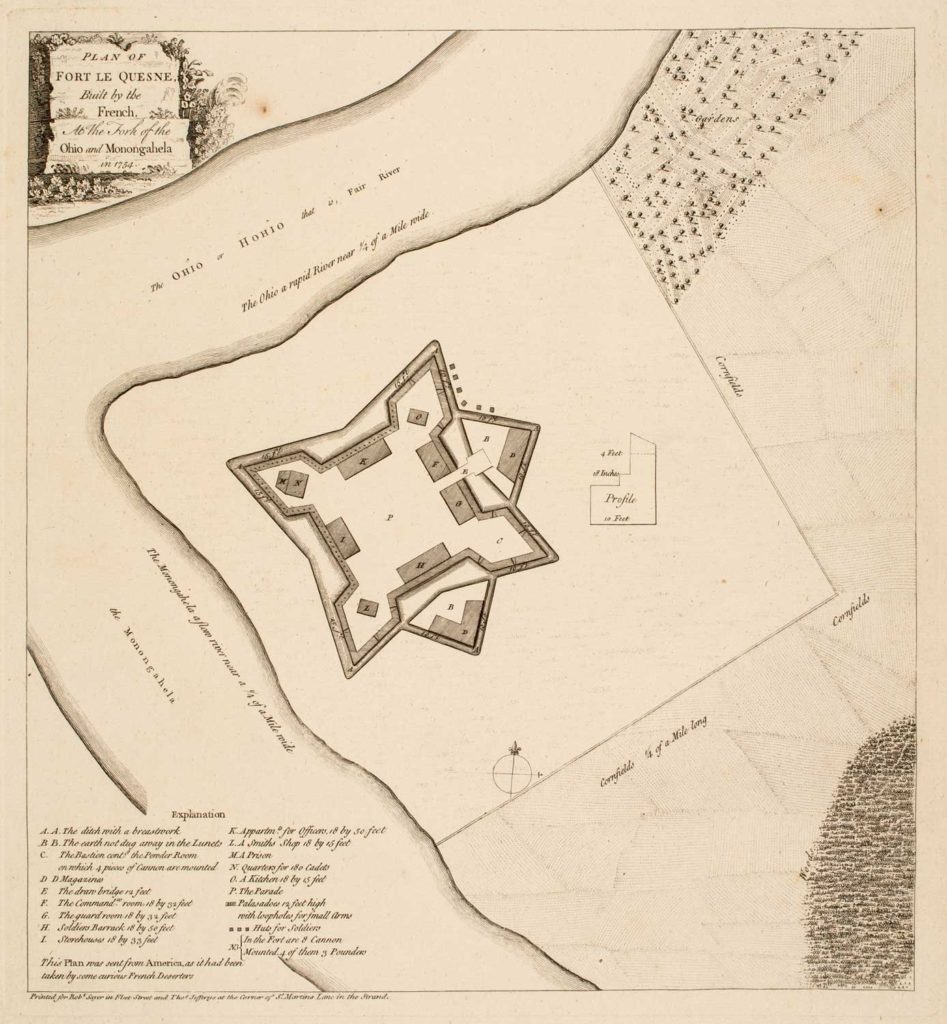

The Seven Years War largely played out in Europe, but was one of the first global conflicts. By the summer of 1754, the Seven Years’ War had spilled into the American Colonies. The French intended to use their territories in the new world as leverage when the time came to negotiate peace; hoping to trade territory in the Americas for territories in Europe. This strategy required the aggressive expansion of French colonial territories. To this end, the French allied with Native American tribes against the British, thus the North American front of the Seven Years War is known as the French & Indian War.

French & Indian War

Initially Sir Allan was recalled from half-pay as a Lieutenant in March of 1756 to serve with Montgomerie’s Highlanders, then designated as the 62nd (Royal American) Regiment of Foot. Sir Allan was “a great companion of the Earl,” Archibald Montgomerie the 11th Earl of Eglinton19 who raised the 77th Regiment of Foot at the outset of the Seven Years War, and quickly obtained a commission as Captain from Lord Eglinton on July 16 of 1757.9 Sir Allan personally raised a company of 100 men, all said to be from Mull,7 within two weeks.19

Montgomerie’s Highlanders were sent to America to reinforce the Highland regiments3 already participating in the Conquest of Candada3 In November of 1757 the three new companies of the 77th Regiment, including Sir Allan’s, mustered in Glasgow22 and departed for Cork in Ireland where they set sail for North America on December 1.22 They reached Charleston, South Carolina after a twelve-week crossing,23 where they were not received well.23 The Living conditions were very poor7 and consequently many suffered illness.22 After arriving in Charleston, Sir Allan was also appointed Captain-General4 of nine infantry companies.24

The Forbes Expedition

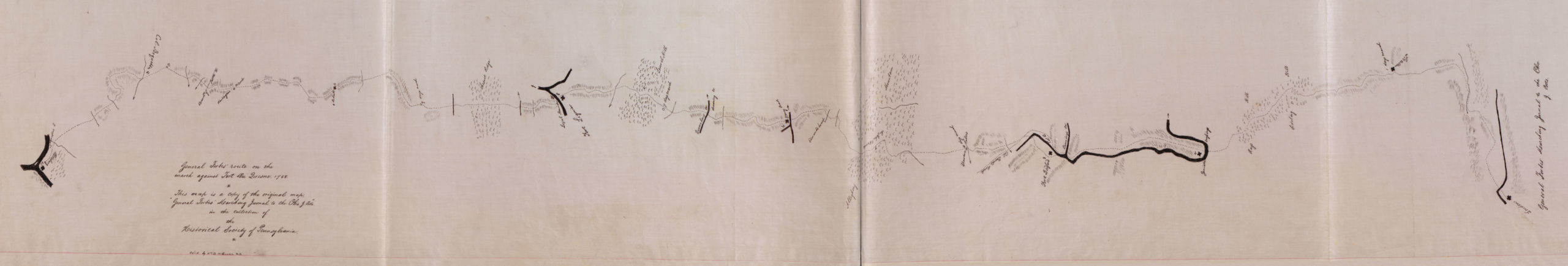

Brigadier-General John Forbes led an expedition to capture Fort Duquesne in 1758. The French built the fort as part in an attempt to claim the entire region surrounding both the Allegheny and Mononhahela river valleys near Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. Sir Allan was with Montgomerie’s Highlanders when they joined Forbes Expedition.

Forbes ordered the construction of a road and series of forts stretching from Carlisle to Pittsburgh which would serve as supply lines and depots for the attack on Fort Duquesne. Construction of the road and forts took most of the summer. Among these was Fort Dewart, a redoubt built by Sir Allan’s company which was also called Maclean’s Encampment.18 Fort Dewart was one of the forts of respite along Forbes’ Road and was built about 200 feet short of the highest point in the Allegheny Mountains. Today, Fort Dewart is the last remaining colonial war-time structure from the Seven Years’ War, or the French and Indian War.

In September of 1758, Forbes sent a detachment of 800 men,22 including 300 Montgomerie’s Highlanders,23 under Major Grant to reconnoiter Fort Duquesne, take prisoners, and strike fear in the French. Unfortunately the raid was outnumbered and ended in disaster. 270 British soldiers were lost or captured.23 The French learned from their captured prisoners that Forbes’ forces were close and far stronger than their own.

Knowing they were outnumbered, the French destroyed Fort Duquesne with explosives on November 24th of 1758 rather than endure siege and capture.22 Before their retreat, the French executed all their prisoners.22 One account noted, On the night of November 24th the men heard a tremendous explosion. Next day they came in sight of the smoking ruins of Fort DuQuesne, blown up and burned. No enemy was in sight – only a row of grisly stakes erected by the Indians. On each one was the head of one of Grant’s detachment and a Scotch kilt tied around its base.

22

Sir Allan was present at the capture of Fort Duquesne. In December of 1758 Montgomerie’s Highlanders marched back to Pittsburgh22 before the battalions dispersed between Lancaster, Fort Mercer, Fort Ligonier, and Long Island to pass the rest of the winter.23 Forbes commanded approximately 8,000 men during the expedition, among them was Colonel George Washington, who took part in the expedition and retired his commission shortly thereafter; the Forbes Expedition was the last military action Washington participated in as a British Officer.

The Annus Mirabliss

The success of Forbes’ expedition was followed by a year of military victories for the British both in North America and the West Indies; 1759 is remembered as the Annus Mirabilis, or Year of Miracles.

Sir Allan was with Montgomerie’s Highlanders in July of 1759 when all its companies were mustered at Albany, New York.23 Once assembled, they marched toward Lake George to join General Jeffery Amherst to join the campaign on Fort Ticonderoga.22 During this campaign, Sir Allan participated in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, Fort St. Frederic, and Fort Niagara.7

Following their success, two divisions of Montgomerie’s Highlanders were sent to continue the campaign and took part in the capture of Quebec,25 whether or not Sir Allan was among them is unknown. These victories played a key role in preparing for the capture of Quebec in September of 1759 and the ultimate Conquest of Canada.

In a letter dated June 19th, 1759 Major Alexander Campbell wrote, “Sir Allan Maclean is doing very well, and is much esteemed. If I survive the campaign I shall be more full on the subject. When the Knight gets a little Drink, he swears that he can scarce know the difference betwixt a Breadalbane Campbell and a M’Lean. I hope if we live to go home to have no discredit to my tutory of him.”19

In October, half of Montgomerie’s Highlanders returned to Crown Point, where they had captured Fort St. Frederic earlier that year, and built Fort Crown Point.22 It is likely that Sir Allan helped build the fort7 before the two halves of his regiment rejoined in Claverack in the upper Hudson River Valley where they made winter camp.22

Anglo-Cherokee War

The British built Fort Prince George and Fort Loudoun as part of Govenor James Glen’s treaty between the Cherokee and the Creek.26 The Cherokee initially wanted the forts to protect them from their enemies, the Creek; however over time, the Cherokee eventually came to view the forts more as a threat to Cherokee sovereignty than as a protection from their enemies.26 Distrust between the British Troops and the Cherokee erupted in 1758 into the Cherokee Uprising. By February of 1760 the South Carolina Commons House asked for British Troops to help quell the uprising.

Sir Allan was among the 12,000 men sent by Amherst in response to South Carolina’s call for help. On the 8th of March in 1760, Sir Allan along with 600 other Highlanders boarded ships in New York bound for Charleston.22 They arrived on April 1st to find that no preparations had been made for their mission.22 They set up a temporary headquarters in Moncks Corner23 and began provisioning themselves for an expedition to relieve the forts and subdue the Cherokee by razing their towns and crops. At the end of the month, the British Troops marched out of Moncks Corner. After marching for nine days, they stopped to rest in Congarees for 17 days before continuing to Fort Ninety-Six near the Saluda River. Colonel Montgomerie cursed the shameful backwardness of this province in every particular.

22

On June 2nd in 1760, Montgomerie’s men arrived at Fort Prince George.23 They continued inland toward Fort Loudoun, but were ambushed at Tessuntee,22 the mountain pass five miles from Cherokee village of Echtoe.22 The ambush, remembered as the Battle of Echoee, forced Montgomerie, who was himself wounded, to retreat back to Fort Prince George.23 Montgomerie returned to Charleston, burning Cherokee villages and crops along the way; though he claimed Cherokee defeat and that September rejoined Amherst in New York,26 Major James Grant, Montgomerie’s second in command,23 would later be sent by Amherst to “to chastise the Cherokees [and] reduce them to the absolute necessity of suing for pardon.”

27

Return Home

Sir Allan returned to Charleston with his regiment in August of 1760,23 where news of the death of his wife, Una, reached him. He immediately took a leave of absence7 and returned to Scotland to make arrangements for the well-being of his daughters who lived there.

With the Conquest of Canada completed,4 Montgomerie’s Highlanders were sent to the West Indies,22 thus rejoining them became very difficult, so Sir Allan joined a regiment being raised from independent companies by Colonel Charles Fitzroy, 1st Baron Southampton.1 Sir Allan obtained a commissioned as a Major in the 119th (Prince’s Own) Regiment of Foot on June 25th of 1762.9 The 119th readied for deployment in Ireland,28 but the Peace of 1763 eliminated the need for further military action. Sir Allan remained with the 119th until it was reduced at the end of the Seven Years War in 1763.7 In all, 54 additional regiments were raised for the British Army specifically for the Seven Years War; after the Treaty of Paris was ratified in February of 1763, all but 2 were disbanded.28 Sir Allan retired on half-pay19 to Mull7 and subsequently was promote to Lieutenant-Colonel on May 25th of 1772.9 Sir Allan retired from his commission at the rank of Colonel4 though he had not been in active service since 1763.7

Reclaiming Brolas

When Archibald Campbell, 1st Duke of Argyll, seized the Duart estate in 1689,3 he also took possession of the Brolas estate. Campbell claimed it as part of the Duart estate7 under a dubious agreement signed a century earlier by Sir Allan to settle a debt bond incurred by Sir Lachlan in 1634.4

In 1770 Sir Allan initiated what would be a lengthy and expensive lawsuit3 against John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll, for the recovery of the titles and lands of Duart and Brolas.7 Sir Allan retained the well known lawyer, James Boswell and MacLaurin to represent him in the suit.3 Sir Allan’s suit was backed by Hugh Maclean of Coll,19 with Allan Maclean of Drimnin as the nominal pursuer—a technicality that strengthened their standing as Allan of Drimnin had not turned out in the ‘45 Rebellion against the crown.19 Allan of Drimmin was also the primary force in raising funds to defray the costs of the suit.19

Our Enemies have our places

And they do not care for us

Though we are polite to them

Our hearts are cold

– A Maclean bard, 178919 –

Sir Allan’s suit against Argyll was decided on the 2nd of July in 1777,19 The decision was a partial victory for Sir Allan, retaining the titles of Duart and Brolas19 but only the lands of Brolas.4 Reluctant to comply with the ruling the Duke of Argyll was compelled in 1783—nearly 20 years after the suit was initiated4— to restore disputed lands to their lawful owner.7

Nicholas Maclean-Bristol noted, “without the lands, the title of Duart became empty. The basis of the contract between clansman and chief, granting land to kinsmen in exchange for service, had disappeared.

“19 It would be nearly two centuries before the Maclean Chiefs again lived in the home of their ancestors. Despite this, Sir Allan famously stated, “Ged tha mi bochd tha mi uasal; buidheachas do Dhia is ann de Chlann ‘Ill Eathain mi,” which translates from the Scots Gaelic, “Though I am poor I am noble; thank God I am a Maclean.”

Retirement

Sir Allan retired to Inchkenneth, near the Isle of Mull, rather than in Canada where he had applied for land that was due him for service in the Seven Years War.8 The small island leased by the Chief7 was only a mile long and half as wide; it was as close as he could live to Duart.4 The Island had been set as the seat of the Macleans of Brolas in 1748,8 as such it had been the the home of his mother, Lady Brolas, until her death.8 His immediate family and servants, were the only inhalants of the island.3

Though his only source of income in retirement was his military pension, it must have been generous enough to support his lifestyle and famous hospitality.4 It is said that, Sir Allan “maintained the dignity and authority of his birth, living in plenty and with elegance.”3

Visitors were regularly entertained at Inchkenneth,5 and Sir Allan was known as much for his hospitality as for his friendliness and courteousness.24 Among the guests at Inchkenneth were the English philosopher and moralist, Dr. Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck, lawyer and author.

Their visit in mid-October of 1773 is recorded in his Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides.3 Boswell and Johnson were quite taken with the Chief, his daughters, and their pleasant island home. Boswell noted in his Journal that Inchkenneth was furnished with unexpected neatness and convenience, practiced all the kindness of hospitality and refinement of courtesy.

5 Johnson was so delighted that he wrote a poem in Latin about his hosts and their island.9

On the little island in the land of his ancestors, Sir Allan passed the remainder of his days.1 On the 10th of December in 1783,29 Sir Allan died at Inchkenneth;7 he was beloved and revered by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance.1 He was buried in the north-east corner and against the south wall of the ancient St. Kenneth’s Chapel on Inchkenneth3 in an enclosure reserved for the Macleans of Brolas.5 Sir Allan’s death marks the last engagement of the Maclean-Campbell feud, though ill feelings between the clans would continue for centuries.19 Sir Allan died without heir, his only son died in infancy,1 thus the baronetcy and chiefship passed to his cousin, Hector, who also descended from Hector Og.4

References

* Lord Maclean of the Jacobite Peerage

- Seneachie. An Historical and Genealogical Account of the Clan Maclean from Its First Settlemnt at Castle Duart in the Isle of Mull to the Present Period. London: Smith, Elder and Co. 1838. 228-230. Print. ↩︎

- The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour. Edinburgh: T.C. and E.C. Jack, 1904. 102. Print. ↩︎

- Maclean, J.P. A History of the Clan MacLean from Its First Settlement at Duard Castle, in the Isle of Mull, to the Present Period. Cincinnati: R. Clarke, 1889. 225-229. Print. ↩︎

- Hoey, Brian. MacLean of Duart: The Biography of ‘Chips’ Maclean. Twickenham: Country Life, 1986. Print. p168-169. ↩︎

- Anderson, William. The Scottish Nation volume 3. London: A. Fullarton & Company, 1877. p43. Print. ↩︎

- White, Alasdair. Clan Maclean Cadet Branches and Their Chieftains. N.p., 29 June 1999. ↩︎

- Mclean, A. Sinclair. The Clan Gillean. Haszard and Moore: Charlottetown, 1899. 468-470. Print. ↩︎

- Currie, Jo. Mull: The Island & Its People. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2000. Print. ↩︎

- Maclean, J.P. An Historical Account of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America Prior to the Peace of 1783. Cleveland: The Helman-Taylor Company, 1900. 389-393. Print. ↩︎

- Ferguson, James. Papers Illustrating the History of the Scots Brigade in the Service of the United Netherlands,1572-1782. Edinburgh: University Press by T. & A. Constable, 1899. Print. ↩︎

- “Issue 9567.” The London Gazette 20 June 1756. 2 ↩︎

- Promotion to Captain was not gazetted, but must have happened as he was a later a Major. ↩︎

- Promotion to Major was not gazetted, but is referred to in Sir Allan Maclean’s promotion to Lt-Colonel. ↩︎

- “Issue 11275.” The London Gazette 15 Aug. 1772. ↩︎

- Wilson, James and Fiske, John. Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography, Volume 4.New York, D. Appleton and Company. 1887. Print. ↩︎

- Mair, Robert H., ed. Debrett’s Baronetage and Knightage 1879. Library Edition Vol. 71. London: Dean & Son, 1879. Print. p290. ↩︎

- Dod, Robert P. The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of Great Britáin and Ireland for 1863 Including All the Titled Classes Twenty – Third Year. Whittaker and Company, 1863. 393. Print ↩︎

- Siwy, Bruce. “Fort Dewart Oldest Surviving Structure From French and Indian War.” Daily American. Schurz Communications Inc., 29 Oct. 2012. Web. 02 Mar. 2015. ↩︎

- Maclean-Bristol, Nicholas, From Clan to Regiment. South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, 2007. 626. Print. ↩︎

- “The Officers of Drumlanrig’s Regiment, &c.”. The Scots Magazine Edinburgh: W. Sands, A. Murray, and J. Cochran, July 1747. Print. p351. ↩︎

- Kay, T. An Historical Account of the British Regiments Employed Since the Reign of Queen Elizabeth and King James I in the Formation and Defence of the Dutch Republic, Particularly of the Scotch Brigade. London, 1795. p78. Print. ↩︎

- Patterson-Costello, Martha. “Travels of the 77th Regiment.” John Paterson (circa 1735 to 1808). N.p., 30 Nov. 2011. Web. 02 Mar. 2015. ↩︎

- McCulloch, Ian. Sons of the Mountains: The Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War, 1756-1767. Toronto: Purple Mountain Press, 2006. Print. ↩︎

- Hardy, Mary. A Brief History of the Ancestry and Posterity of Allan Maclean, 1715-1786, Vernon, Colony of Connecticut. Berkeley, California: Manquand, Printing Co., 1905. p20. Print. ↩︎

- Keltie, John Scot. A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments. Edinburgh: Grange Publishing Works, 1885. Print. ↩︎

- Edgar, Watler. South Carolina: A History. Columbia, South Carolina: Univ of South Carolina Press, 1998. 204-209. Print. ↩︎

- Anderson, Fred. >Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf, 2000. Print. ↩︎

- Pollock, Arthur. “Sketch of the Formation and Service of the Various Regiments of the Line Raised and Disbanded Since the Commencement of the Seven Years’ War in 1756,” The United Service Magazine v65. London: H. Hurst, 1851. 555. Print ↩︎

- Maclean, J.P. An Account of the Surname of Maclean, or Macghillean: from the Manuscript of 1751. Xenia, Ohio: The Aldine Publishing House, 1914. 9. Print. ↩︎

Uncited Sources

- Maclean, J.P. Renaissance of hte Clan Maclean. Columbus, Ohio: The F.J. Heer Printing Co, 1913. Print. p111-144.

- Boswell, James. The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson, LL. D.. London: Office of the National Illustrated Library, 1852. 253-273. Print.

- Peckham, Howard. The Colonial Wars 1689-1762. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1964. Print. p178, Print.

Article updated 2015 MAR 24